There's No Such Thing as Political Inaction

Or, 'Designing Thought': unveiling the role of binary oppositions and negative space in society, mind and design

In Western thought traditions we often act and define reality on the basis of fundamental binary oppositions, sometimes known as dichotomies. If you're not familiar with this concept, learning to recognize these oppositions is a powerful conceptual tool for understanding social reality. As you begin to identify them, you'll notice their presence everywhere. Whether you approach it through the more conventional idea of a 'dichotomy' or 'false dichotomy', or delve into the less common but impactful notion of a 'dialectic', binary oppositional thinking permeates contemporary discourse. It serves as the bedrock for many of the polarized and seemingly unresolvable conceptual challenges that confront modern society.

When confronted with these seemingly intractable oppositions, a common response is to disengage from either side, viewing this as a way to avoid taking responsibility for resolving the dichotomy. Alternatively, individuals might feel compelled to align firmly with one ‘side’, often leading to unwavering, sometimes fanatical devotion to that perspective. Fewer individuals recognize that achieving a deeper synthesis is essential to navigating a resolution between deeply rooted binary oppositions. This raises the critical question: how can such a synthesis be achieved? What is needed is a shift in the fundamental tools of human conception to discern the reality underlying oppositions and to identify the space for syntheses to emerge.

Oppositional thinking, and even awareness of this human tendency, can be found in some of the earliest intellectual products of the human mind, reaching deep into antiquity. In the 19th and 20th centuries, numerous social theories and philosophies attempted to more systematically make sense of binary oppositions and their role in human thought. In the 20th century, various disciplines in the social sciences, literature, psychology, comparative mythology and others all underwent profound transformations influenced by a philosophical approach known as 'structuralism'. This school of thought played a pivotal role in shaping many contemporary social theories by shedding light on the fundamental binary oppositions that underpin social life and the overall 'structure' of society.

These contemporary theories proposed to 'decode’ the rules and structure of society, similar to how a linguist might decode the rules of grammar in a sentence, or a physicist tries to discern the natural laws that govern the universe. A pivotal realization was that human thought and social relations have revolved in one form or another around key binary oppositions throughout history. There are obvious and commonly posed binary oppositions, such as 'good vs evil' or 'light vs dark', ‘truth vs falsehood’, which you're likely familiar with. Others include matter vs spirit, masculine vs feminine, order vs chaos, society vs individual, progress vs tradition, and so on and so forth.

Of course, since their elaboration within modern social theory, the idea or proposed importance of binary oppositions has faced significant challenges, particularly in the theories of post-structuralism, feminism, and other schools of thought. Nonetheless, despite significant scholarly efforts to complicate the relevance of binary oppositions in society and to propose alternative models, it is hard to escape the sway that binary oppositions hold over human thought. Consequently, it remains a compelling question to explore why human beings gravitate towards such thinking, particularly in Western traditions. Are we invariably reliant on such oppositional thinking? Are there alternatives to such ways of thinking? How do we move beyond simplistic binaries, especially when they impede progress?

This brings us to the idea of 'negative space' or why there is no such thing as 'inaction' in the face of binary opposition. As it turns out, the idea of 'negative space' may actually offer one form of thinking that helps us overcome deeply entrenched binary oppositions.*

*Note: If binary oppositional thinking truly does have such a hold on human thought, this will make it challenging to even sketch out an alternative. So soon as we escape the snare of one dichotomy, we fall prey to another. The example that follows will try to provide an intuitive example we can use to navigate more complex matters later on. Of course, even when we 'understand' how we might go about an alternative mode of thinking, the original model isn't automatically 'banished' as a default. It takes active effort to apply this lens, as we’ll see. Let's begin.

What is ‘negative space’?

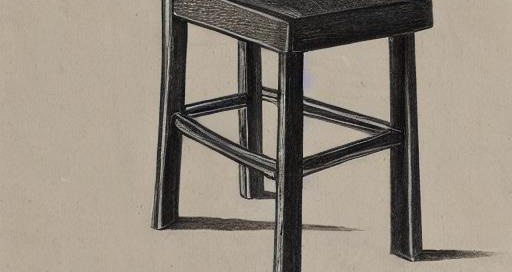

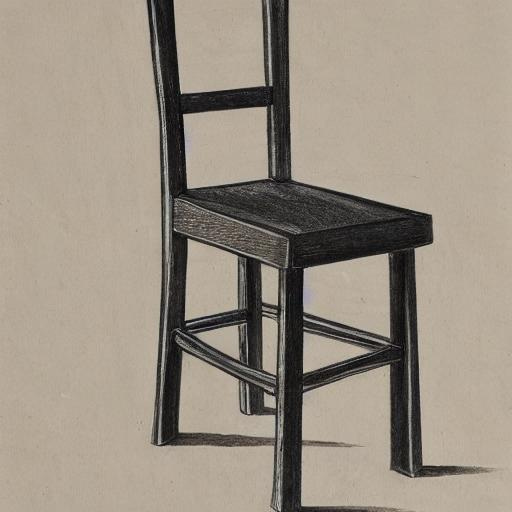

To develop a better understanding of this approach to reorienting our thinking, let's explore the concept of 'space' and 'negative space' through an example. Consider a chair. Let's say we wish to beautifully and accurately represent this chair in the form of a drawing. The obvious place to start is to take pen to paper and begin by drawing the outlines and features of each leg, the back of the chair, the contours of the seat, any artistic features of the wood or fabric, and so on. Indeed, this is the first impulse and default approach to say we have successfully represented the chair on paper. This method, which involves adding lines and gradually crafting a representation of the chair, is what we can call a "positive" depiction of the object.

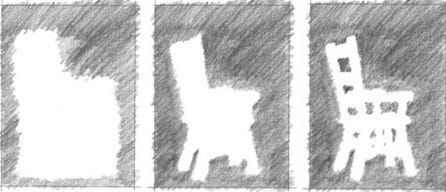

No matter your artistic skill, you can probably at least draw an image that is recognizably chair (I hope - if not please add YOUR image to the comments and we will decode it together). But as anyone who's practiced art knows, it is actually rather challenging to develop an excellent sense of proportion, an accurate perception of space, and the artistic sense of how to draw something with intent. You could spend countless hours refining your chair-drawing skills and genuinely still see improvements in representation many hours into the learning process. But eventually (probably quickly) you will hit a plateau. In the world of art, a counter-intuitive but excellent practice for developing the deeper artistic skills to progress beyond some of those early barriers is to deliberately avoid drawing the object itself. Instead, draw the space that the object 'inhabits'. In other words, don't draw the spatial proportions and attributes of the object itself, focus on drawing the 'negative space' that the object occupies within its surrounding environment. Exclude any interior details or features of the object; only represent the space it takes away from its context.

As an artistic practice, this is a superb way to refine your skills and elevate your talents to the next level. But there's actually something even more profound at play here. What if we applied this principle not only to physical objects and art but to concepts and other features of reality? What you'll begin to see is that between, within, and behind oppositional decisions, there exists an alternative space—a negative space—that can offer intriguing opportunities for resolving complex problems and navigating the dynamic flow of life around you. This capability can reshape your understanding and open entirely new perspectives on the world around you. Let's consider some examples to begin learning how to recognize and apply this alternative mode of thinking.

Negative Space Thinking and the Binary Oppositions in Society

At the level of society, significant inertia often hinders critical decision-making processes on matters crucial to the benefit, health, functioning, and needs of the whole. But where does this inertia actually arise from? Let's consider the material infrastructure of a country as an example. Regardless of the many underlying rationales, theories, factions, and ideologies involved, any collective decision typically gives rise to two fundamental groups: 'those in favor' of a particular plan and 'those not in favor'. In a scenario where one side advocates investing trillions in infrastructure while the other opposes it, binary oppositional thinking naturally leads us to perceive these two choices as: you either support or do not support the proposal. This tends to be seen as 'act' or 'do not act'. These opposing viewpoints often acquire additional layers of binary oppositions, often imbued with moral significance. One side is 'good', one is 'evil'. One represents 'progress', or 'modernity' the other signifies 'backwardness' or 'tradition'.

But how would our concept of 'negative space' come into play here? Is the side that opposes moving forward with developing new infrastructure the 'negative space' side because they are not proposing something? No, this isn't the case. While they are technically 'against' a positively proposed action, this does not constitute the negative space in such a situation. The binary oppositions posed here revolve around 'yes' and 'no', but 'no' is still a positively articulated position. To interpret it is 'action' and 'inaction' is actually inadequate, as we’ll see shortly. Instead, it is more accurate to frame it as 'acting to accomplish' and 'acting to not accomplish' the desired change.

Indeed, the 'inaction' of the 'no' bloc is actually best considered as an action. It is indeed a deliberate choice, not a lack of one, and certainly not a safe space where no one bears responsibility for the consequences, such as decrepit infrastructure and collapsing bridges. In the same way, those in the 'yes' faction are indeed deliberately proposing both the benefits of new infrastructure and the potential downsides such as cost, resource demands, planning challenges, and effectiveness. It just so happens that it is mostly easier to attribute those other consequences when one side is framed as 'actors' and another as 'inactors'.

What this dynamic reveals is that notable aspects of any complex decision-making are often overlooked and unrecognized when we pose two opposing camps as 'actors' and 'inactors'. Those labeled as 'inactors' have an asymmetric benefit from shifting blame away from their affirmative decision (to not act) by claiming they merely 'haven't made a decision'. By feigning inaction, they shift the personal attribution of consequences away from themselves: 'so-and-so built new highways' and 'so-and-so did not build new highways' have different salience with respect to how we think about who caused what. In the most challenging examples, such as multigenerational endeavors like infrastructure development or other matters related to the long-term prosperity of society, by posing as 'inactors' those in the 'no' camp shift the attribution of the consequences to the long march of time where humans are less apt to assign blame: the thinking becomes 'our highways decayed over the last 50 years' and not ‘these coalitions and groups that prevented investment in infrastructure and stopped us from improving/replacing and allowed decay to occur’.

As we can see, 'negative space' thinking should not be confined to one aspect of a binary opposition, particularly not to those in favor and those opposed. Instead, it enables us to uncover the hidden consequences that both 'yes' and 'no' decisions entail, shedding light on the uncharted territory that decisions *inhabit*, often going unrecognized. Once you begin mapping out these dynamics, we begin to discern the repercussions and how such framings permeate society, stunt human thinking, and contributes to the seemingly insurmountable inertia that prevents human progress. The more complex and daunting the problem, the more we may fall prey to this dynamic. This is particularly evident in the generational and seemingly insurmountable challenge of climate change, a problem that clearly stretches human capacity far beyond its breaking point. In this light, it is no surprise that it is uniquely the most intractable and most threatening crises affecting human society. However, our inability to engage in sustained systematic thought beyond basic oppositions is not limited to the societal level matters such as these, it affects every level of social interaction.

Negative Space Thinking & Institutional Policy

To delve into this further, let's explore a more familiar context: the level of the organization and its policies. In prior posts, we’ve considered the idea that organizational policies are not ‘just so’, they are actually embedded expressions of underlying assumptions & ideology. When it comes to policy development, 'negative space' thinking allows us to recognize that the absence of policy is also not synonymous with 'inaction'. In fact, lack of policy is just as, if not more, significant than what policies are actively implemented. Similar to how not saying something can convey as much or even more than literally saying something, 'negative space' thinking allows us to reveal subtle and counterintuitive consequences of this absence, often the source of deliberate or unintended harms, inefficiencies, lack of progress, and inertia.

To comprehend these dynamics, we can apply a useful framing that distinguishes between ‘conscious’ and ‘unconscious’ articulation of policy and decision-making. This will aid in interpreting and understanding the actions and functioning of organizations and institutions and illumine the otherwise unrecognized 'negative space'. In a sense, we can interpret a policy and its *intended* consequences as an explicit consciousness within an institution of a defined set and pattern of actions and the series of outcomes an institution wishes to promote. The policy is an attempt to articulate how the institution envisions and intends for that pattern to unfold. But it also has an unconscious dimension: those unintended consequences of the policy that go unrecognized or unpredicted. This is the negative space of an actively present policy.

A lack of policy follows similarly: the lack of policy can be viewed as an institution or organization being 'unconscious', that is, letting a pattern of action/outcomes emerge according to other forces or alternatively, *not* allowing a certain pattern to emerge. Conventional binary thinking would view this again as 'inaction' rather than 'action', but this can also be viewed through the lens of what the institution is 'conscious' of. In the same way that 'no' is actually a positively affirmed action, not an inaction, a lack of policy can also be attributed as an action and can be implemented in ways that represent the consciousness and lack of consciousness of an organization.

This becomes particularly problematic when we recognize that this 'lack' of institutional consciousness can be weaponized when it represents a deliberate, willful ignorance hiding behind the supposed 'lack' of recognition of whatever pattern that is unfolding (represented in the lack of a policy, for instance). The notion of 'conscious' articulation allows us to conceive of an institution that is actually just unaware that a certain pattern of action is underway within that organization, or that they may claim to be unaware but who 'hide' behind the lack of policy. This can shift and misattribute responsibility, and may significantly stall progress and resolution. It becomes most concerning when grave harm or abuse is being perpetuated and we fail to attribute accountability for such egregious actions, especially when a collective group is at fault rather than just one or a series of individuals. In fact, the dynamic relies precisely on our inability to contend with how blame should be distributed at the level of collective accountability, given that are we far more accustomed to dispensing 'individual-level' blame. While that is the more dangerous form, the more common form that goes unrecognized is at the level of 'dark patterns' in institutional functioning that promote conflict, cause unnecessary friction, stall effective functioning, and lead to other notable problems. To explore this in a practical context, let's examine an example related to institutions and the design they pursue.

Negative Space Thinking & Design Principles

I was engaged in a tense discussion on my campus some time ago, regarding excessive noise and disrespectful interactions between groups of students in a shared space. At the heart of it, according to the graduate students advocating for their needs before representatives of the institution, was the undergraduate students' use of the space as a social area contradicted the graduate students' need for a coworking space. The space in question was a newly constructed building that blended study, social, and working spaces. The framing given in the conversation was that competing priorities arose from different users of these spaces and that the groups had inherently conflicting purposes (the problem also appeared to me to be tinged with an 'us vs them' mentality).

The problem of space design and conflicting priorities is a common challenge often encountered with the 'open office' designs popular in the last few decades. The administration responsible for this space cited some familiar design-based reasonings popular in recent years that informed the creation of the space and its layout: inter-group collaboration. fostering culture & community. equitable design. Te The aggrieved students (the direct users of the space) rightfully shared feedback on how those decision decisions had direct (negative) consequences on how people inhabit the space. Notably, the other 'party' (undergraduates who were 'causing' the issues) were absent from this meeting.

These challenges may already strike a chord with those familiar with design thinking You may already see some of the ways 'negative space' thinking might help us interpret this scenario. Building design offers a great example of space and 'negative space', both in the literal sense just like the chair example, but also in the conceptual sense we've been exploring so far. Simply put, rooms and designs have space allowances and constrictions and offer a particular arrangement that obviously determines in many respect how that space is used - akin to the lines that form the attributes of the chair. But they also determine things in less obvious ways through the space - literal and conceptual - those decisions inhabit and take up.

Take, for example, a dining space. The width and length of a dining area, interruptions in the space allotted for it, various thresholds and passageways in the space including walls, openings, and windows - even decisions of materials used - all these can make it easier or more difficult for the users of a space to find adequate space to dine or do whatever else it is they wish to do in that space. In certain cases, these decisions could even negate the envisioned core function of the space. If space constrictions make it too challenging, users might even decide to dine in another space not specifically designed to be dined in, while neglecting the intended space. Whatever the intent of the action of the design in deciding some feature, we can see that the decision not to use the space doesn't just fall on the user, or even the direct intentions of the designer, but encompasses also the 'negative space' created by the designer's action or inaction and the implicit consequences that arise. In some circumstances these outcomes may be inconsequential, in others they can be disruptive.

The dining area in the building I'm describing is central to each floor, with open office cubicles on one or both sides of the dining area. As a result, the noise generated by socializing in the dining area easily spreads and interrupts the core purpose of the working spaces on either end. If, instead, the dining areas were only on one end of the building or enough suitable natural boundaries were in place the noise would only interrupt those closest to it or those directly in the space. Similarly, a hard barrier between the spaces would limit crossover between the two areas. The centrality of the dining area, the lack of barriers, and other features of that space are all examples of 'negative space' consequences of the design decisions at play.

Like organizational policies, designers explicitly envision and implicitly condone particular norms and functioning for how a space is used through their design choices. Space design, whether through the presence or absence of some feature, positively defines these norms and functions in many tangible ways. But in this process, designers also consciously or unconsciously define other ways the space becomes filled. Through the impact of 'negative space', their decisions shape, allow, suggest, define, neglect, or constrict how people and groups inhabit the designed space and even what *doesn't* occur in that space.

For the building relevant to this discussion space I was in, each floor is interconnected by a spacious open central staircase making it easy to switch floors and interact between groups/departments. This was a deliberate design decision. The positioning of the stairs, connecting the floors at the kitchen and dining area, inherently promotes social interactions because dining is a universally natural opportunity for social engagement. This social function was also an explicit vision of the designers. Obviously, these social areas can and are used as study and work spaces, but the predominant pattern of human interaction is one of shared eating and is intended to facilitate connections. However, the central location and proximity to workspaces immediately adjacent to the dining area challenge the intended purposes of both the social and workspaces, leading to a fundamental contradiction. A series of unintended consequences follow. It disrupts the nearby working spaces structured as open-air cubicles for a different kind of interaction (professional collaboration) that presupposes certain acceptable and unacceptable norms of behavior. Meanwhile, the dining space attracts a substantial number of people - the quality of socializing and even the beauty of the space becomes a positive feedback loop drawing in others who are not the intended users of the space. This further causes an overflow from the dining area into the co-working spaces and nearby meeting rooms and cubicles. Consequently, these areas then inherit the social atmosphere and high-energy interactions from the social environment, encroaching on the work collaboration areas.

The ultimate outcome resulted in conflicting purposes and interpersonal contention stemming from both explicit design decisions, but also the lack or abdication of design decisions to resolve unrecognized discontinuities in space and purpose. It illustrates the challenge of follow-through from the explicit design decisions of the space into the ways the constructed space is actually built and then inhabited. We see how the negative space that the design decisions 'take up' guide the users of the space in subtle ways. Clearly, other decisions are needed to alleviate the issues when they reach enough of a boiling point that the users of the space request institutional corrective action. The proposed intervention was to ban certain groups from even using the space (a policy), but little attention was paid to the decisions already made about how the space was built and functions.

We can see how even at the level of one space within a building of one department, the dynamic at play here turns out to be a fundamental disjuncture between two posed opposites and the positive and negative implications of those opposites. The premise of 'negative space' thinking is that better awareness of not just the positive more readily apparent aspects but also the 'negative' underlying implicit aspects - in both their conscious and unconscious, intended and unintended forms - will help us to attain a deeper synthesis or higher level of awareness that, ideally, can resolve the binary opposition or dichotomies. But are these binary oppositions that we are trying to overcome just present in the world around us, or do they also characterize our own internal world and interpersonal experience?

Negative Space Thinking, Our Own Personal Life

Turning to a more conceptual level, human interactions are patterned in a similar way at the level of foundational moral principles, values, virtues, and ethics.

Again, we are used to thinking in terms of two basic opposed principles, and this often leads us to intractable and unresolved conflicts. In reality, it is often another value that has to resolve the difference rather than simply mediating or overcoming the one with the other, the positive with the negative. If we are conditioned to think solely in terms of the opposites we miss this fundamental necessity. For example, we commonly recognize that love and hatred are opposed principles and are fundamentally tied in some kind of continuum. But when hate prevails (or love is absent) the solution isn't always some overpowering act of love because hatred does not always yield to its opposite. Instead, we must think in terms of remedy and remediation, and this is where the intuition offered by 'negative space' thinking comes in. How do we remedy hatred and restore harmonious conditions? If we read the outlines or negative space of the situation we may realize that the solution actually lies in another factor: trust. The key term here is restitution. In the negative space of hatred and love when restitution is called for, trust is the missing element. When trust is broken, how can love be re-established?

Digging deeper, we may find that the necessary principle for restitution is best framed as 'justice'. Although love and hatred remain the basic binary opposition, the solution to hate may be justice rather than love, inasmuch as justice is a necessary precondition to loving relationships founded on trust. If hate has caused someone to grievously harm another, the 'negative space' lens suggests that simply asserting that love (as the opposite of hate) must be present to resolve the discord would overlook the fact that the conditions for love must first be restored. It highlights the space that hate takes up (or that love has left in its absence). In other words, the resolution of the binary opposition comes not from the action of the one on the other but from the synthesis that comes from understanding that 'negative' space: recognizing that hatred and hateful acts cloud any possibility for love, and then lack of justice prevents any restitution of that love. The restorative power here lies in justice, restitution, and renewal of basic trust (trust that one won't harm the other, that one won't be harmed again, trust that those who harm others face consequences, etc).*

*A caveat: certainly these dynamics can also be framed in terms of forgiveness, mercy, reciprocity, harmony, and more. The realities behind these principles and values are far more complex than any simple elaboration can allow, and the exploration is not intended to promote formulaic thinking. Rather, the goal is to illustrate the deeper level of discernment and shifts in understanding needed to transcend basic oppositional thinking.

To close, lets revisit the original question on how we respond to oppositions: is there such thing as inaction in the face of a binary opposition and is there a way to 'not participate within highly polarized decisions?

While a comprehensive exploration of this topic is beyond our current scope, we have examined how binary oppositional thinking perpetuates powerful dichotomies that continue to permeate Western discourse. In recent centuries, Western thought has been dominated by what could be called 'naive literalness' or ' vulgar materialism'. For our purposes, we might describe these as a domineering rigid, formulaic adherence to thinking of things as they are and only as they appear to be. That truth is derived solely from a mechanistic understanding of any object under study. Such impulses were bolstered by the shift towards scientific & rational thought that began in the 1600s, followed by the rise of 'empiricism' and 'physicalism' as dominant philosophical perspectives from the [[18th century]] onward (the Enlightenment and the Scientific Revolution). There is no question that science is a uniquely powerful system of thought and leads to incredible transformations in human society. However, construing the entirety of existence through a literalistic, mechanistic lens, which suggests that our knowledge relies solely on the senses and one's rationality - a very circumscribed view of rationality at that - is almost ironic given that so much of Western thought in these past few centuries has (supposedly) been about getting passed the 'ignorant literalism' of Judeo-Christian faith traditions and ancient mythologies. That is, at least according to the certain perspectives that pose a fundamental opposition between science and religion, faith and reason. But is this view of rationality and mechanistic thinking even inherent to scientific thought or is this an ultimately limited conception of how scientific discourse operates? Where, precisely, does this attachment to an overbearing materialism come from? Why is it that it is so hard to imagine the negative space around the chair, the space the chair inhabits, rather than the dimensions and materiality of the chair itself? Why did it take so long for Western science, steeped though it was in individualism, to even conceive of the matrix of the culture and the collective in a full-fledged way that doesn't just reduce it to mechanistic or reductionist views?

I will leave those questions for future exploration.

What I will propose is that we will encounter highly polarized binary oppositions frequently within our own lives and in the world around us. Some of these may end up being 'false dichotomies' and can be dismissed as such, while others may prove more resilient. Our initial aim should be to learn to identify these oppositions when they arise and recognize the way our base tendencies encourage us to engage in unfruitful patterns of thought around them. Secondly, we must begin to develop the ability to engage in new, more fruitful ways of thinking that assist us in overcoming these oppositions. One potent approach is to perceive through the lens of 'negative space'. Consequently, we recognize that 'inaction' is as much a form of action as silence is a means of expressing what words often cannot convey. We begin to discern the conscious and unconscious, the intended and unintended consequences of doing and not doing certain acts, at more and more subtle levels. The notion of political 'inaction' becomes far more intricate than it initially appears. We begin to appreciate how these dynamics manifest at various levels within society and even our own selves, and how this fundamental oppositional pattern of thought lies at the core of many of our steps and missteps. This pattern of thought is driven by internal and external factors. The capacity to overcome its frailties is by no means a straightforward endeavor. Nevertheless, hopefully, the benefits it yields will become self-evident.

‘Wow, you made it to the end! This one was a doozy. Thanks for reading Tabula. If you found value in what you read, consider subscribing and sharing with friends that might find this useful. Have a thought, question, or comment that this post inspired? Join the conversation below and make your unique contribution to this community.